The Genealogist’s Internet

The Genealogist’s Internet |

One of the most obvious features of the internet that makes it good for genealogical or indeed any research is that it is very large, and the amount of material available is continually increasing. It is impossible to get an accurate idea of the size of the web, but it is reasonable to assume that it is at least tens of billions of pages, and that figure does not include any data held in online databases.[1] But the usefulness, or at least accessibility, of this material is mitigated by the difficulty of locating specific pages. Of course, it is not difficult to find the websites of major institutions, but much of the genealogical material on the web is published by individuals or small groups and organizations, which can be much harder to find. For more extensive websites, there’s the problem that the wealth of material on a particular topic may not be evident from the home page. Also, since there is no foolproof way to locate material, a failed search does not even tell you that the material is not online.

The standard tool for locating information on the web is a search engine. This is a website that combines an index to the web and a facility to search the index. Although many people do not recognize any difference between directories, gateways and portals on the one hand, and search engines on the other, they are in fact very different beasts (which is why they are treated separately in this book) and have quite different strengths and weaknesses, summarized in Table 19-1.

Table 19-1: Comparison of directories, etc., with search engines

| Directories, gateways and portals | Search engines |

|---|---|

| Directories and gateways list websites according to general subject matter. | Search engines list individual web pages according to the words on the page. |

| Directories are constructed and maintained by humans. In the case of genealogy gateways you can assume the compilers actually have some expertise in genealogy. | Search engines rely on indexes created automatically by ‘robots’, software programs which roam the internet looking for new or changed web pages. |

| Directories and particularly specialist gateways for genealogy categorize genealogy websites intelligently. | While some search engines know about related terms, they work at the level of individual words. |

| Directories are selective (even a comprehensive gateway like Genuki only links to sites it regards as useful). | Search engines index everything they come across. |

| Directories, offering a ready-made selection, require no skill on the part of the user. | The number of results returned by a search engine can easily run into six or seven figures, and success is highly dependent on the searcher’s ability to formulate the search in appropriate terms. |

| Gateways often annotate links to give some idea of the scope or importance of a site. | A search engine may be able to rank search results in order of relevance to the search terms, but will generally attach no more importance to the website of an individual genealogist than to that of a major national institution. |

These differences mean that directories, and particularly gateways and portals, are likely to be good for finding the home pages of organizations and projects, but much less well suited to discovering sub-pages with information on individual topics. Even genealogy directories with substantial links to personal websites and surname resources probably don’t include more than a fraction of those discoverable via a search engine. A directory or gateway might give you a link to the home page of a body like the Society of Genealogists, but only a search engine will take you straight to the page for the opening times. And if you are looking for pages which mention the name of one of your ancestors, there is little point in using a directory or gateway. You have to use a search engine.

There are dozens of different search engines, but the most widely used general-purpose search engines are four in number:

In fact Yahoo Search uses the same web index as Bing, so their search results will be very similar (but, oddly, not always identical).

For a comprehensive list of search engines, see Wikipedia’s page ‘List of search engines’, which links to individual articles.

In spite of the more or less subtle differences between them, all search engines work in basically the same way. They offer you a box to type in the ‘search terms’ or ‘keywords’ you want to search for, and a button to click on to start the search. The example from Yahoo Search shown in Figure 19-1 is typical. Once you’ve clicked on the ‘Search’ button, the search engine will come back with a page containing a list of matching web pages (see Figure 19-2), each with a brief description culled from the page itself, and you can click on any of the items listed to go to the relevant web page. Search engines differ in exactly how they expect you to formulate your search, how they rank the results, how much you can customize display of the results and so on, but these basics are common to all.

Search engines generally report the total number of matching web pages found, called ‘hits’, and if there is more than a page (typically 10 or 20), it will provide links to subsequent pages of hits. (In Figure 19-2, you can see this information in a very small font just beneath the search box.) Usually the words you have searched on will be highlighted in some way.

Figure 19-1: The Yahoo Search home page at <search.yahoo.com>

Figure 19-2: Results of a search on Yahoo Search (with ad blocking switched on)

On some search engines, at the top of the search results or alongside the first results, there may be adverts from websites with material more or less relevant to your search terms. For any search on the word [genealogy] or genealogical records like [parish registers], for example, these are most likely to be for some of the commercial data services described in Chapter 4. You will not see these if you have an ad blocking tool enabled in your browser.

Your success in searching depends in part on your choice of search engine, which is discussed on p. 347, but is also greatly dependent on your skill in choosing appropriate search terms and formulating your search.

In this chapter I have put search terms between square brackets. To run the search in a search engine type in the text between the brackets exactly, but don’t include the square brackets themselves. Note that the figures given for the number of hits have indicative status only — they were correct when I tried out these searches, but the indexes used by search engines grow daily, so you will not get identical results. Also, there is no way to verify the accuracy of the figures except where they are under a thousand or so. But the differences between the various types of search and formulation should be of the same order.

There are actually several different types of search offered by search engines. In the basic search — the one you get if you don’t select any options and just type in words to be searched for — the results will include all web pages found that contain all the words you have typed in the search field. This means that the more words you type in, the fewer results you will get. If you type in any surname or place-name on its own, unless it’s a fairly unusual one, you will get thousands of hits. So it’s always better to narrow down your search by entering more words if possible. This type of search is called an AND search. AND and OR are just the most commonly used parts of a general technique for formulating searches called Boolean logic.[3]

Search engines automatically include some alternatives when looking for common words, as they have information about related word forms and common misspellings. If you search on [ships] or [shipp] the result will include pages with the word ‘ship’; searching on [walk] will find pages with ‘walking’. Search engines call this technique ‘stemming’ and it is used by default in all searches. If you don’t want the variant forms included in search results, prefix your search term with what is called an ‘inclusion operator’. In most search engines the + sign is the inclusion operator, and it effectively means ‘this word must be in the results and in this exact spelling only’. Irritatingly, in October 2011, Google stopped using the + in this standard way — to achieve the same effect in Google you now have to put each individual word between inverted commas.

Among other things, inclusion is a useful way of excluding variant spellings if you have a surname that is also a common noun or similar to another word: a search for [+Bridges] will not find pages which only have the singular form ‘bridge’; a search for my ancestor [Edward Weimark] on Bing brings up pages on Edward of Saxe-Weimar, which can be got rid of with [Edward +Weimark].

But if you want to carry out a search which includes other alternatives, you cannot do it just by including all the forms you can think of. For example, if you were looking for the baptisms for a particular family, you might be tempted to search on both ‘baptism’ and ‘baptized’ along with the surname, perhaps throwing in ‘christened’ and ‘christening’ for good measure. But each extra word reduces the number of matching pages found. On Bing, therefore, [Hollebone baptism] produces 30 hits, [Hollebone baptized] 11 hits, while the combination [Hollebone baptism baptized] produces not more than 30, as you might have hoped, but many fewer — only seven. And [Hollebone baptism baptized christened] gives only two, both from the full texts of surname dictionaries.

The same will happen if you give alternative surname spellings: for example Google gives around 4.3 million hits for [Waymark] and 586,000 for [Wymark], and 1.2 million for [Whymark] and 90,000 for [Weymark], but [Waymark Wymark Whymark Weymark] produces just 81, a tiny number of pages which have all four variants. Adding a fifth variant, [Weimark] reduces this to just seven hits. Of course, if you are searching for pages which actually discuss the variants of this particular name, you might be happy with a small number of results, but if you are looking for all pages that might mention someone with any variant of this surname, you will not want to miss pages which have only a single spelling.

The AND search is not suitable for looking for alternatives, unless you really do require pages that have all of them. What you need instead is an OR search, which will retrieve all pages containing at least one of the search words.

All the main search engines offer the option of doing an OR search. There are normally two ways to do this. First, all search engines have an Advanced Search page: there will be a link to this somewhere near the search box on the main page, often to the right, though in Yahoo Search (Figure 19-1) you need to click on the ‘More’ link, and on Bing you can only get to the advanced search from a page of search results, not from the home page.

The advanced search will offer you a wide variety of things to specify about what you are looking for but near the top should be options to ‘look for all of the words’ and ‘look for any of the words’. The first of these is for words which must be included, the latter where any one of the alternatives you give will do. Figure 19-3 shows how to do this on Google’s Advanced Search page at <www.google.com/advanced_search> and that at Yahoo is very similar.

Figure 19-3: An OR search on Google’s Advanced Search page

Bing does not use a comprehensive form like Google and Yahoo, which show all the options at once. Instead, you enter each group of search terms and select whether you want:

Figure 19-4 shows how to enter the terms for an OR search. When you click on the ‘Add to search’ button your search terms are translated into the correct syntax in the search field.

Figure 19-4: Creating an OR search with Bing

The other way to create an OR search — and one which is much quicker once you know what you’re doing — is simply to type in the correct formulation directly in the search field. Strictly, the correct way to do this is shown in the following example:

[Hollebone AND (baptism OR baptized)]

But given that the default search is an AND search, this is equivalent to

[Hollebone (baptism OR baptized)]

which is what Bing search requires. Bing also permits the use of the ‘pipe’ symbol | instead of OR.

However, many search engines are more relaxed. For example, Yahoo and Google only require the OR, not the AND or the parentheses:

[Hollebone baptism OR baptized]

All of them also seem to accept the strict syntax, so that will be the best approach if you can’t find specific information about this topic on their help pages.

You can use the same principles to construct more complex searches:

[Robinson AND (genealogy OR “family history”) AND (Nottingham OR Notts) AND (cobbler OR cordwainer)]

which Google would allow you to enter as

[Robinson genealogy OR “family history” Nottingham OR Notts cobbler OR cordwainer].

Often you will find yourself searching on a word that has several meanings or distinct uses, in which case it can be useful to find a way of excluding some pages. The way to do this is to choose a word which occurs only on pages you don’t want, and mark it for exclusion, which most search engines do by prefixing with a hyphen. For example [Bath Somerset -tub -tap] would be a way to ensure that your enquiry about a city in Somerset was not swamped by results for plumbing suppliers.[4]

There is one very common problem when searching for geographical information which this technique can help to alleviate: names of cities and counties are used as names for ships, regiments, families and the like; also, when British emigrants settled in the colonies they frequently reused British place-names. This means that many searches which include a UK place-name will retrieve a high proportion of irrelevant pages.

If you do a search on [Gloucester], for example, you will soon discover that there is a Gloucester County in Virginia and in New Brunswick, a town of Gloucester in New South Wales and in Massachusetts (not far from the town of Essex), and you probably do not want all of these included in your results if you are looking for ancestors who lived along the Severn. Then there is HMS Gloucester, the Duke of Gloucester, pubs called the Gloucester Arms, towns with a Gloucester Road, and so on. Likewise, if you’re searching on [York], you certainly do not want to retrieve all the pages that mention New York.

Obviously it would be rather tedious to do this for every possibility, but you could easily exclude those which an initial search shows are the most common, e.g. [Gloucester -Virginia] or [York -“New York”]. (Another way to cut down on these irrelevant results would be to search for [Gloucester England], though this will miss many personal genealogy sites, where the country tends to be taken for granted.)

Another case where this technique would be useful is if you are searching for a surname which also happens to be that of a well-known person: a search such as [Woolf -Virginia] will reduce the number of unwanted results you will get if you are searching for the surname Woolf, and do not want to be overwhelmed with hundreds if not thousands of hits relating to the most high-profile bearer of the name, who is likely to dominate the first few pages of results.

Unfortunately, if you are searching for a surname which is also a place-name, e.g. Kent or York, there is no simple way to exclude web pages with the place-name, though on p. 349 I suggest a technique for restricting your hits to personal genealogy websites.

A further problem arises from the attempts of the search engines to spot mistakes in your search terms, discussed above. If you enter something that seems on the face of it to be an error, Google may give you the results for the corrected form and offer your original as an alternative (try [Hodgeson]), or, worse, the results may mix the corrected and uncorrected forms (try [Childs]). Some of their efforts are rather surprising: if you search on Bing for [Dallaway], 99 per cent of the results are for [Callaway]! As mentioned above, the way to prevent this is to use the inclusion operator.

The reason for putting the Boolean operators AND/OR in upper case, incidentally, is that these are small words which search engines normally ignore, so-called ‘stop words’: [Waymark OR Wymark] finds 4.8 million hits on Google, [Waymark or Wymark] finds only 6,570 — the ‘or’ has been ignored and the alternative spellings treated as an AND search.

Other stop words include ‘the’ and ‘of’: if you search for [Alfred the Great] or [Isle of Man], you should find that the number of search results is very similar to those for [Alfred Great] or [Isle Man].

You can enforce the inclusion of a stop word by using the plus sign, but for searching on names, places and occupations, this is not likely to be very useful — if you have a stop word in a name, e.g. John of Gaunt, Robert the Bruce, Isle of Man, it is better to treat the entire name as a phrase, as explained in the next section, in which case any stop word is not ignored.

Another important issue when using a search engine is how to group words together into a phrase. If you just type in a forename and surname, for example, search engines will treat this as an AND search on the two components.

This may not matter, especially if you are looking for a site by name, as search engines tend to put near the top of their listings those hits which include all search terms in the page title. This is particularly the case with organizations and projects, so, for example, a Windows Live search on [Manorial Documents Register] produces around 113,000 hits, but the MDR area on The National Archives’ site, which is the official home of the MDR, is at the top of the list (see Figure 19-5).

Figure 19-5: A search for [Manorial Documents Register] on Google

This will also work for many two-word terms used in genealogy: you should expect all the top results for [poor law], [window tax] and [parish register] to be relevant. Even with relatively obscure occupational terms such as [fellowship porter] or [boot sprigger], you should find that most of the top results are not just pages where the two words happen to occur separately.

However, you can’t count on this, and even with two-part place-names, which you might expect a search engine to recognize, your results may include many irrelevant hits. On Bing, for example:

(Google, incidentally, is better at recognizing these two place-names.)

But if you want to be sure that your words are treated as a complete phrase, you need to place them between inverted commas, e.g. [“South Norwood”] or [“John Smith”] or [“National Register of Archives”].

However, there is a downside: although you are getting more manageable and correct results, the phrase search will miss pages with “Smith, John” or “John Richard Smith”, so it is not an unmixed blessing. It will also inevitably miss “John, son of Richard and Mary Smith”, though with present technology this is simply beyond the capabilities of search engines. Even so, with a reasonably unusual name, the phrase search can produce a list of hits short enough for each one to be checked — for example, a search for [“Cornelius McBride”] on Google produces only 1,240 hits, compared to 11 million for [Cornelius McBride]. As soon as you add a place-name, this becomes a manageable set of results.

If you’re looking for something very specific, you may find it immediately, as with the search in Figure 19-5. This is particularly the case if you are searching on the name of a high-profile site. Otherwise, however, you shouldn’t assume that your initial search will find what you want and produce a manageable list of results. If, for example, you are looking for individuals or families, or trying to find information on a particular genealogical topic, it is likely that you will have to look at quite a lot of the hits a search engine retrieves before finding what you are looking for. This makes it important to refine your search as much as possible.

The previous pages offer some advice on formulating your search, but however well you formulate it for the first run, you will often be able to refine it once you have looked at the initial results. Search engines provide a search box with your search terms at the top of each page of hits, so it is very straightforward to edit this and re-run the search.

Some search engines offer facilities to refine your search within the results you have already retrieved. In Google, clicking on the ‘Search within results’ link at the bottom of a results page takes you to another search page where you can specify a narrower search with additional words. However, this does not actually do anything clever — it just adds the new terms and re-runs your original search. If you know how to formulate searches, these facilities don’t offer anything extra.

Apart from taking care in formulating your query, there are a number of other things to bear in mind if your searching is going to be successful and not too time-consuming.

First, the better you know the particular search engine you are using, the better the results you will get. Look at the options it offers, and look at the Help or Tips pages. Although I have highlighted the main features of search engines, each has its idiosyncrasies. And while it is quite easy to find what a search engine will do, sometimes the only way to find out what it will not do is to see what is missing from the Help pages. It is also worth trying out some different types of query, just so you get a feel for how many results to expect and how they are sorted.

If you carry out searches on your particular surnames on a regular basis, it can be worth adding the URL of the results pages to your bookmarks (Firefox) or favorites (Internet Explorer), making it easy to run the same query repeatedly. This works because in most search engines the browser submits the search terms as an appendage to the URL, which is then shown as the web address of the first page of results. Bookmarking this page will allow you to retrieve the entire URL and then re-run the search.

There is one simple browser technique which will save you time when searching. Once you have got a list of search results that you want to look at, open each link you follow in a new window or tab so that the original list of search results remains open. (On Windows browsers a right mouse click over the link will bring up a menu with this option; on the Macintosh shift+click). Otherwise, each time you want to go back to your results the search engine will run the search all over again. Another useful trick for a long page of results is to save the page to your hard disk so that you can explore the hits at your leisure later.

Search engines can be used for finding other types of material online in addition to web pages. This material falls into two broad categories, which are generally dealt with in distinct ways.

First, there are files with textual material but which are in a proprietary document format rather than the public HTML format used for web pages. All the main search engines index such material for a number of file formats, notably Adobe Acrobat (PDF) files, described in more detail on page 60, and Microsoft Word files. This is important because many bodies put longer-term official information online in PDF format.

The content of such files is usually included automatically in the search engine’s index, so you do not need to specify a particular file type when searching. However you will be able to choose ‘file type’ on the advanced search page of most search engines.

Multimedia files are generally handled differently, and the tendency is to have a separate search facility for each format. As you can see in Figure 19-1, Yahoo Search has separate tabs for images and video (audio is available from the ‘more’ link), while Google offers the images, groups (i.e. newsgroups, see p. 324), news, and maps tabs at the top of the home page.

Of the various multimedia file types, those of most interest to genealogists will be the graphics files of scanned or digital photographs. An overview of the sorts of photographs you can expect to find online is given in Chapter 17.

When searching for images, you can’t simply use the standard facilities of the search engines, since these look for text. Although any search results will include pages with images on them, particularly where there are relevant captions, this may not be obvious from the list of search engine results. This might be a way to find sites or pages that are devoted to photographs or postcards, but it will be a time-consuming way to find individual photographs.

Google has an excellent image search facility at <images.google.com>. The search results pages show thumbnail versions of the images which match your search criteria — moving the mouse over an image produces a slightly larger version with some text from the source page, while clicking on an image takes you to the original page from which the image comes — Figure 19-6 shows the results of a search for [Deptford dockyard].

Figure 19-6: Search results in Google Images

Figure 19-7: Google’s Advanced Image Search

Mostly you will just get a normal search box, but if there is an advanced image search this should allow you to be more precise about the sorts of image you want, such as that from Google shown in Figure 19-7.

The Technical Advisory Services for Images has a very comprehensive review of image search facilities, including both general and specialist search engines, at <www.jiscdigitalmedia.ac.uk/stillimages/advice/review-of-image-search-engines>. Although it is now a few years old, and some details will be out of date, it remains a useful introduction to the topic.

Other resources for finding images are discussed in Chapter 17.

Although search engines are mainly used for searching the whole web, they can also be used to search individual websites. Since most major sites have their own search engine, the value of this may not be immediately obvious. But there are two advantages: you don’t have to get to grips with a new search engine every time you visit a new site, and the big search engines often have much more sophisticated search facilities than those on individual sites, particularly the smaller ones. Using a general search engine, you can use the advanced search options to do more complex searches, specify a date range for pages retrieved, look for particular filetypes, etc. However, the external search results may not be as complete or as up-to-date as those from the internal search engine of a well-managed site.

Most search engines allow you to specify a particular site as one of the advanced search options — look on the advanced search page for a field labelled with the words ‘site’ or ‘domain’. Just as with the OR search, you will see that if you know how to formulate it, you can carry out this type of search without going via the advanced search page, by using a special keyword in the basic search. The keyword varies from one search engine to another: in most it’s the keyword site followed by a colon, and then the site to be searched, e.g.

[“tithe maps” site:www.nationalarchives.gov.uk]

In fact, you do not need to specify a complete site, but can restrict your search to a ‘domain’. For example, a search with [site:nationalarchives.gov.uk] will include all National Archives sites, not just the main one. You can specify even less: [site:gov.uk] will conduct a search on pages from any UK government website, including those of local authorities. So the following search would be a good way of finding out which local record offices have projects to digitize tithe maps:

[“tithe maps” project site:gov.uk]

Even if you want a specific county, it will often be quicker to type, say,

[“tithe maps” project Staffordshire site:gov.uk]

than to find the site for Staffordshire’s local authority or CRO, visit it, and then use its own search facility to find the tithe maps project.

However, there are some sites which can’t be searched in this way: Genuki and WorldGenWeb, for example, are distributed services, which means that material is spread among many different servers. A search on [site:genuki.org.uk] will find only material which is on Genuki’s main server and miss much of the county material which is in fact held elsewhere. Genuki, has its own search (see p. 352), which is not affected by this problem (since, naturally, Genuki’s search engine has a list of all the Genuki servers).

It is important to bear in mind some of the limitations of search engines. The most significant is that no search engine indexes anything like the whole of the web. A 1999 study found that no search engine covered more than 16 per cent of the web.[5] This study may be a decade old, but there has not been any revolution in search engine technology to suggest the results are no longer broadly valid. For this reason, when you cannot find something with a search engine, it does not mean it is not there.

Also, do not expect all results to be relevant. Even a fairly precisely formulated query may get some irrelevant results. A particular problem will be pages with long lists of names and places — these will inevitably produce some unwanted matches. For example, a surname interest list which contains an Atkinson from Lancashire and a Chapman from Devon would be listed among the results for a search on [Chapman Lancashire]. Particularly if you do not include terms like [genealogy] or [“family history”], or something that occurs more frequently on genealogy sites than elsewhere — [“monumental inscriptions”] or [“parish register”], for example — you will get many irrelevant results. And, of course, searching for a fairly common surname may retrieve numerous genealogical pages that are nothing to do with your own line.

There are ways to cut down on irrelevant results if you are looking for a particular family. The more precise your geographical information the better: if you know your Chapman family came from Exeter, search not for [Chapman Devon] but for [Chapman Exeter Devon]. (Keep [Devon] in — you do not want Exeter College, HMS Exeter, Exeter in New Hampshire, etc.) If you search on both surnames of a married couple, even if they are individually quite common, you are much more likely to get relevant results, for example [Chapman Atkinson Exeter Devon genealogy]. If you use full names, all the better — even [“John Smith” “Ann Williams”] finds only 208,000 pages on Google; if you add [Yorkshire], it comes down to around 6,000! A village name will cut it down even more. You will still tend to retrieve a few surname listing pages, but there is little that can be done about that.

Finally, the web is full of spelling errors. For example, Google finds over a quarter of a million pages which mention a supposed county of ‘Yorskhire’. In this sort of case, most search engines will spot that you probably meant Yorkshire and give you the results for the correct spelling, though of course this means you may miss pages put up by distant cousins who don’t use a spelling checker. The search engines often seem able to spot obvious misspellings for even quite small places, but you can’t assume they will be as successful with surnames.

Another problem in finding material on the internet, particularly records relating to individuals, is that much of it is simply not available in permanent web pages, which are readily accessible and can be indexed by search engines. This is what is called the ‘invisible web’, ‘hidden web’ or ‘deep web’, and it includes:

The only way to find the information is to go to the site and complete the registration procedure or fill in the search fields. Such material, which will include that provided by the commercial data services and other records covered in Chapters 4 to 6, cannot normally be retrieved by search engines. The same is true for much of the material covered in Chapter 14.

Which is the best search engine depends on a number of factors. The overriding question is: what are you looking for? There are several different aims you might have when using search engines. You might be trying to locate a particular site that you know must exist — you only need one result and you will recognize it when you see it. This is usually a search for a particular organization’s website, or some particular resource that you’ve heard of but can’t remember the location of.

Alternatively, you may be trying to find a good site on a particular topic or any site which might have information on a particular surname, or even a particular ancestor. The difference between this and the previous search is that there is no way of telling in advance what your search will turn up, and probably the search results will include a certain number, perhaps even a lot, of irrelevant sites. Another difference is that in the first case, you almost certainly have some idea of what the site might be called.

With this in mind, there are three main criteria to consider when deciding which search engine to use:

The first of these is the most fundamental. Other things being equal, the search engine with the larger index is more likely to have what you are looking for. However, while this will be very important in looking for pedigree-related information, it will be largely irrelevant if you are looking for something like the Society of Genealogists’ website, which you would expect all search engines to have in their indexes.

Since search engines are constantly striving to improve their performance and coverage, there can be no complete guarantee that what is the most comprehensive search engine at the time of writing will still hold that position when you are reading this. However, Google has been dominant for many years and the difference between it and its nearest rival can be seen from the graphs at <www.worldwidewebsize.com>.

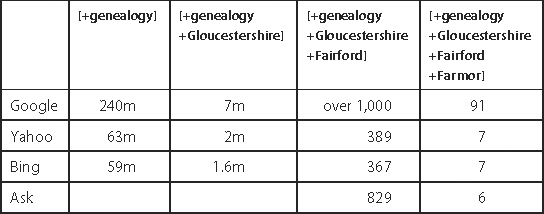

Table 19-2: Hits for [genealogy] on the main search engines (October 2011)

To get an idea of what the differences mean for the family historian, Table 19-2 shows the number of hits for some typical genealogical searches on the four main search engines in October 2011. The figures in the first two columns should be treated with considerable caution (not to mention scepticism) as there is no way to verify their accuracy, and Ask does not give figures for its search results. The figures for the two narrowest searches, however, are based on my manual count of the results, (though Google won’t display more than 100 pages). Overall, there is no reason to doubt the claim that Google is quite significantly ahead of its rivals in terms of coverage.

Unless you get only a handful of hits, one of the issues which will determine the usefulness of search results will be whether the most relevant ones are listed first. In fact, poor ranking effectively invalidates the virtues of a large index — a page which is ranked 5,000 out of 700,000 might as well not be included in the results at all because you’re never going to look at it.

It’s difficult to be specific about how search engines rank their results (since these are valuable commercial secrets) but broadly speaking they assess relevance based on:

Google explicitly uses a popularity rating, giving higher priority to pages which many others are linked to, though probably other search engines do this, too. This is good if what you want are recommendations — which is the best site on military genealogy, say. But if you are searching for surnames and pedigrees, which are probably on personal websites, it may be positively unhelpful, as these will automatically rank lower than well-connected commercial sites which happen to have the same surname on them. Almost any surname search will tend to list the major genealogy sites high up, especially those with pages for individual surnames or surname message boards. Unfortunately, in spite of past experiments in this area, none of the major search engines currently offers any way of controlling how results are ranked.

For personal genealogy pages, the only way I have found of doing this is to include the phrase [“surname list”] in the search terms. The basis for this is that many of the software packages used to create a website from a genealogy database (see Chapter 20) will create a page with this as a title or heading. The results will also include, of course, some non-personal sites such as the county surname lists mentioned on p. 225, but the phrase does not seem to be common on non-genealogy sites, and is less likely to be encountered on commercial genealogy sites.

However, there is an argument that choosing the ‘best’ search engine is not enough. It’s not just that no individual search engine indexes more than half the web. The fact is that each search engine includes in its index some pages which may not be in another search engine’s index at all. And there is a very useful tool which illustrates the size of the problem, the Ranking utility at <www.thumbshots.com/Throw/Ranking.aspx>. This allows you to compare the top 60 hits for a search on any two search engines, and if you try it with something reasonably rare you get a clear indication of the limited coverage.

Figure 19-8 shows the results for the phrase [“bounty migrants”] in Google and Yahoo: of the top 60 hits (the first six pages of results), only 20 per cent of the sites found are common to both search engines. Of course, there are cases where this won’t matter: if you’re looking for a particular site such as that of a genealogy organization, for example. But if you’re searching, as here, for historical information, or for a particular ancestor by name, you could be missing useful material if you only use one search engine.

The moral is obvious: in a comprehensive web search for individual ancestors and matching surname interests, you cannot afford to use only one search engine, no matter how large its index may be.

Figure 19-8: Thumbshots: searches for [“bounty migrants”]

One technique for overcoming the fact that no search engine indexes the whole of the web is to carry out the same search on several different search engines. The easiest way to do this is to add a range of other search engines to your browser’s built-in search facility: in Internet Explorer, click on the down arrow to the right of the search box and select ‘Find More Providers’; in Firefox, click on the down arrow to the left of the search box and select ‘Manage Search Engines’. Once you have done this you can quickly carry out a search on several different search engines in sequence.

The search engines discussed so far have been general-purpose tools, but there are also many special-purpose tools. Some of these are discussed elsewhere in the text. Image search tools are discussed earlier in this chapter. Online gazetteers are dedicated tools for locating places (see p. 253). Chapter 12 covers online catalogues to material which is itself not online. All of these are going to be better for their particular purpose than the general search engines.

Over the years, there have been a number of attempts to create a comprehensive search engine specializing in genealogy. These have generally been short-lived, in part, no doubt, because of the difficulty of compiling a well-defined list of genealogy sites to index. Cyndi’s List has a ‘Search Engines’ page at <www.cyndislist.com/search-engines>, but many of the sites listed are in fact directories and others are limited to searching online pedigrees (these are covered in Chapter 14).

The most recent attempt at a genealogy search engine is Mocavo at <www.mocavo.com>, which was launched in March 2011. In November 2011 a UK version was launched at <www.mocavo.co.uk>. The basic search is free, but an annual subscription of $119.40 gives access to more advanced search options. There is no detailed information on the site about its site selection criteria but it includes many genealogy message boards and blogs as well as more general genealogy sites. Also, there is the option to upload your own family tree in GEDCOM format (see p. 357).

Initially, the site has concentrated mainly on US material and this is the case even for the UK service, so it is not yet very useful for British and Irish genealogy beyond the coverage of message boards, and even here, specifically British services like TalkingScot and British-Genealogy are absent. It includes the main Genuki server at <www.genuki.org.uk> but not Genuki pages hosted elsewhere, and the websites of family history societies and record offices do not seem to have been captured at all. Searching on [Gloucestershire Fairford Farmor], as above, found only six results, all from the Internet Archive.

However, at the time of writing the site is still very new, and no doubt more UK sites will be included. In any case, even with these limitations it is useful to have a search whose results are exclusively genealogical. It should certainly be a more effective tool for finding material on genealogy blogs and the larger message boards than a general-purpose search engine.

The Genuki Search at <www.genuki.org.uk/search> is probably the most useful dedicated search engine for British and Irish family history. Although it confines itself to ‘institutional’ websites with material relevant to the British Isles, its index in fact includes many of the most important non-commercial genealogy sites:

Because of the importance of searching to serious use of the internet and for professional researchers in any field, there are many sites with guides to search engines and search techniques.

Among the many online tutorials, the University of California at Berkeley’s ‘Finding Information on the Internet’ at <guides.lib.berkeley.edu/evaluating-resources>, and BrightPlanet’s very comprehensive ‘Guide to Effective Searching of the Internet’ at <brightplanet.com/images/uploads/SearchEngineTutorialFormatted041218.pdf> are particularly recommended. Rice University has a concise guide to ‘Internet Searching Strategies’ at <library.rice.edu/services/dmc/guides/e-resources>, which, though severely out of date in terms of the search engines mentioned, nonetheless has good advice about general techniques.

Kimberley Powell has a guide to searching specifically for genealogy sites and pages in ‘Google Genealogy Style’ at <www.thoughtco.com/google-genealogy-style-1422365>.

While there are any number of books about searching the web, there is, so far as I am aware, only one current book on the subject specifically for genealogists: Daniel M. Lynch’s Google Your Family Tree (FamilyLink.com, 2008) covers the whole range of Google’s facilities and services from a family history perspective, and three of its 14 chapters are devoted to getting the best out of the search engines.

Next chapter: 20 Publishing Your Family History Online

1 Pandia’s February 2007 article ‘The size of the World Wide Web’ at <www.pandia.com/articles/web-sizel>, which gathers together a number of estimates, concludes that ‘the number of web pages must be somewhere between 15 and 30 billion — and probably closer to the latter’. In July 2008 Google claimed to have indexed one trillion unique URLs — see <googleblog.blogspot.com/2008/07/we-knew-web-was-big.html>. They also claim that ‘the number of individual web pages out there is growing by several billion pages per day’. To put this in perspective: the British Library’s integrated catalogue includes a mere 13 million printed items, with at best probably five billion pages between them.

2 This is Microsoft’s search egine, previously called Windows Live Search and, before that, MSN Search.

3 This topic can be handled only briefly here. For more information on using Boolean expressions for searching, look at the help pages of the search engines or Part 3 of BrightPlanet’s ‘Guide to Effective Searching of the Internet’ at <brightplanet.com/images/uploads/SearchEngineTutorialFormatted041218.pdf>.

4 This hyphen is to be regarded as a substitute for the typographically correct minus sign, which your browser would almost certainly ignore and therefore not submit as part of your search.

5 Steve Lawrence & C. Lee Giles, ‘Accessibility of information on the web’, Nature, 8 July 1999, pp. 107—109 (online at <www.nature.com/articles/21987>).